Hu Shi's "Butterflies": An analysis of the first published poem in colloquial Chinese

15 Oct 2024

This is a partial transcript-cum-show-notes of a presentation i gave for a class on 20th century chinese literature. The topic i had to present on was the birth of colloquial poetry, spearheaded by Hu Shi.

Hu Shi was influential as a poet not because his poems were good, but because he moved to using the vernacular. In this way, he is as important to modern chinese literature as Dante was to italian or Chaucer was to english. On 23rd august 1916 he wrote a poem, “butterflies”. It was the first poem in vernacular chinese that was ever published.

Poetry was important to chinese society because the quality of a poem was seen to be tied to a man’s knowledge of historical context and events and the whole corpus of prior poetry and literature. To write a bad poem was to admit that one was not up to par as a member of the literati.

In conversations with Zhao Yuanren, another chinese person living in america, Hu Shi concerned himself with how the literacy rates of the common chinese people could be improved. One move in this direction was the decision to use western punctuation marks when publishing his scientific magazine “Science”.

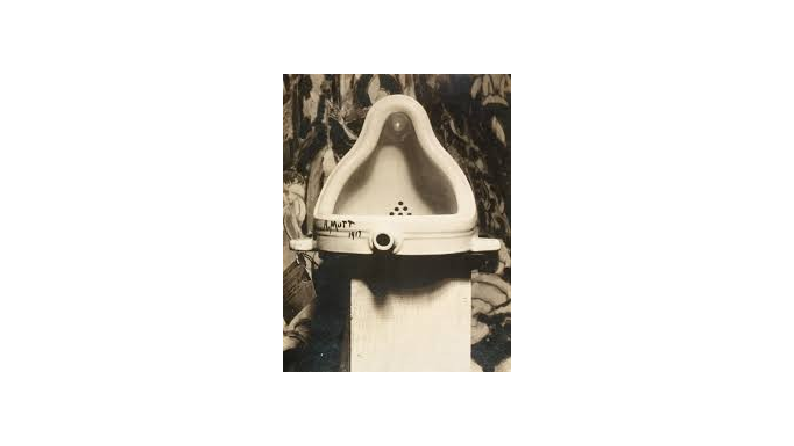

At the same time, Hu Shi was making friends with prominent figures in the american avante-garde art movement, and was exposed to art by Duchamp and Picasso, among others. Although he didn’t come to understand the produced art itself, he appreciated the way that the artists were willing to experiment with what art could be. In the context of chinese poetry, this would mean rejecting the conventions established by the literati in favour of a form that the average person can understand purely through reading and personal reflection on their own experiences, rather than a deep knowledge of a whole ancient culture.

Some of his friends disagreed that vernacular chinese was an appropriate form for writing poetry, to which he responded by composing some private poems in letters. It seems that the main argument against his reform is that it was a slippery slope, which is a common refrain from people who are benefited by a narrow artistic culture. In response, Hu Shi composed Butterflies as a poem in vernacular chinese, by a person who was known to be able to write poetry.

Later on, Zhao Yuanren was influential in the establishment of putonghua as a standardised form of the spoken chinese language, something that he had previously discussed at length with Hu Shi. Hu himself was eventually denounced by Mao and all his papers siezed by the party. His public image was stained, although now many people once again respect him and his work.

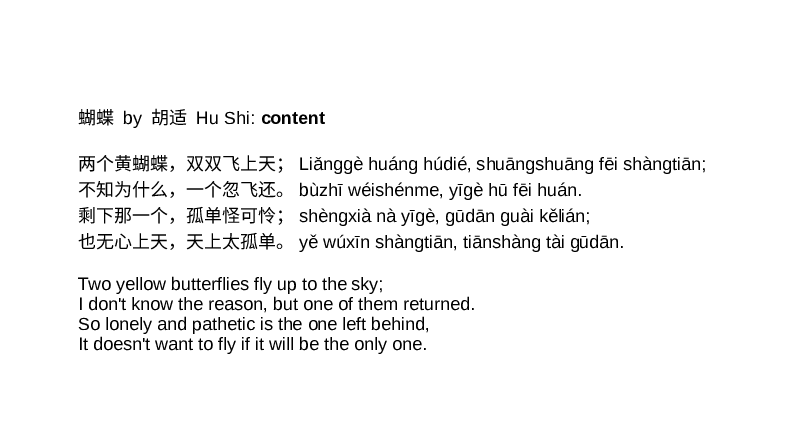

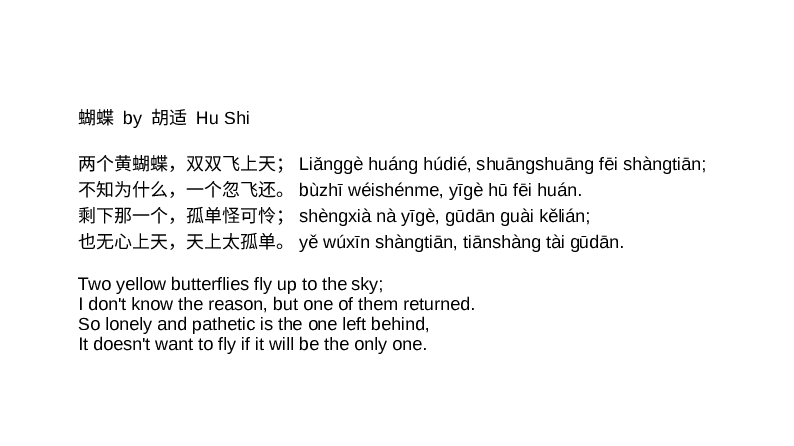

This is the poem we will be looking at:

蝴蝶 两个黄蝴蝶,双双飞上天;Two yellow butterflies fly up the sky, 不知为什么,一个忽飞还。One suddenly flits away, I don’t know why. 剩下那一个,孤单怪可怜;The very sky looks so lonesome, that 也无心上天,天上太孤单。The one left behind no longer cares to fly.

With these focuses…

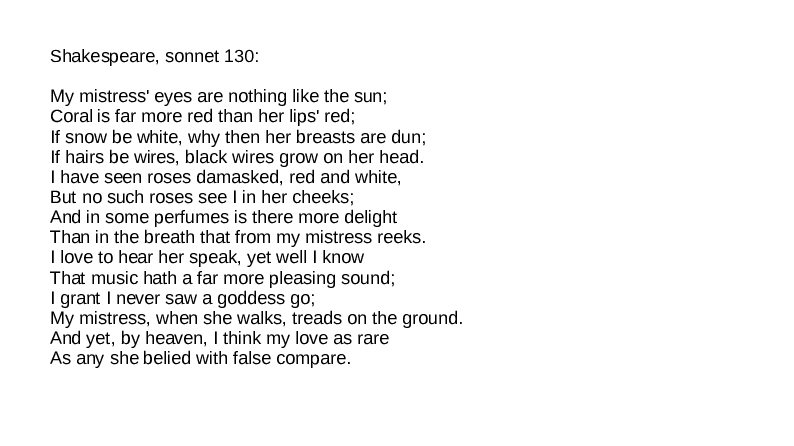

As an example applied to shakespeare…

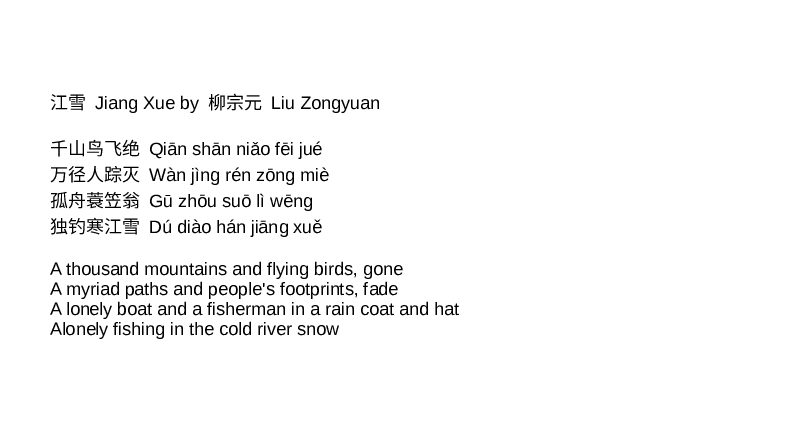

But first, i want to briefly discuss a different poem, a famous tang dynasty shi:

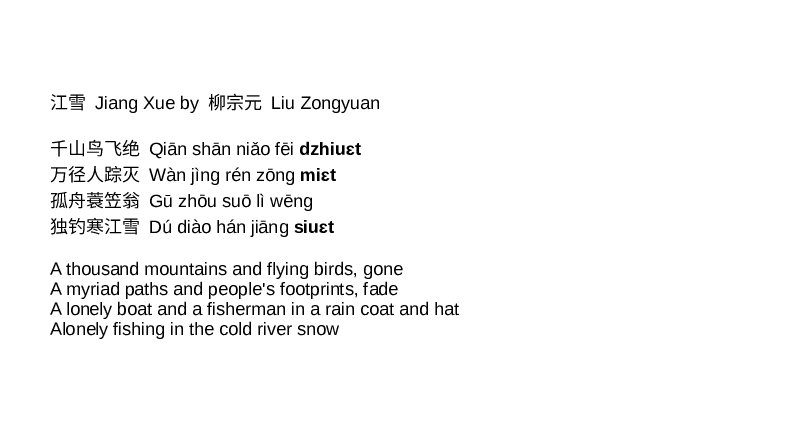

江雪 Jiāng Xuě by Tang dynasty poet 柳宗元 Liǔ Zōngyuán

千山鸟飞绝 Qiān shān niǎo fēi jué 万径人踪灭 Wàn jìng rén zōng miè 孤舟蓑笠翁 Gū zhōu suō lì wēng 独钓寒江雪 Dú diào hán jiāng xuě A thousand mountains and flying birds, gone A myriad paths and people’s footprints, fade A lonely boat and a fisherman in a rain coat and hat Alonely fishing in the cold river snow

Tang dynasty shi are four lines of five characters. A second stanza is often used. In classical chinese, all words are a single syllable, so every character is stressed.

Many people have tried to translate this poem into english, and the terse form of classical chinese makes this quite difficult, especially when respecting the rules of english grammar. My quick attempt at translation above highlights something i consider to be an important aspect of the poem that is overlooked in most of the translations i have seen, which is that the first four characters of the two lines in the first stanza set a scene, and then that scene is inverted by the final character. It’s difficult to do this with such dramatic effect in english.

I have also placed less emphasis on specific numerical quantities than a lot of translations, because i think the importance is that these numbers are large than that they are specific, and have chosen the lesser used word myriad, which does happen to mean ten thousand, instead of that more common form.

I have also used a coined word “alonely” which has the unfortunate effect of introducing a sort of word play, but which to me fits better than any other word i could think of in english.

The second half of the poem also features an inversion, but instead of inverting each line, it inverts the first half by focusing in the micro level of a single human within the macro level of a vast description of nature. This reflects the aesthetic style of many ink wash paintings, a style characteristic of the tang dynasty period. Nature is ambivalent towards humanity, and despite the impermanence of life within the world, a human is still taking advantage of the materials and food provided within nature to get by in life.

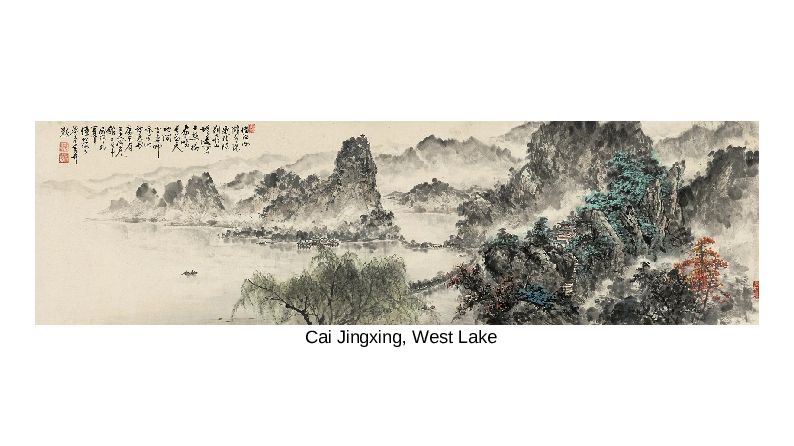

(See Cai Jingxing’s West Lake)

With that in mind, let’s look again at Hu Shi’s poem butterflies:

两个黄蝴蝶,双双飞上天;Liǎnggè huáng húdié, shuāngshuāng fēi shàngtiān; 不知为什么,一个忽飞还。bùzhī wéishénme, yīgè hū fēi huán. 剩下那一个,孤单怪可怜;shèngxià nà yīgè, gūdān guài kělián; 也无心上天,天上太孤单。yě wúxīn shàngtiān, tiānshàng tài gūdān.

Two yellow butterflies fly up to the sky; I don’t know the reason, but one of them returned. So lonely and pathetic is the one left behind, It doesn’t want to fly if it will be the only one.

I have also quickly translated this one because i think that the translation in the essay doesn’t do a good job at showing some of the significant features of this new style. Notably, the rhyming is poor and the rhythm is off. It also changes the order that information is revealed to the reader which i have tried to avoid, but for the sake of rhyme i have switched the order of the two clauses in the third line.

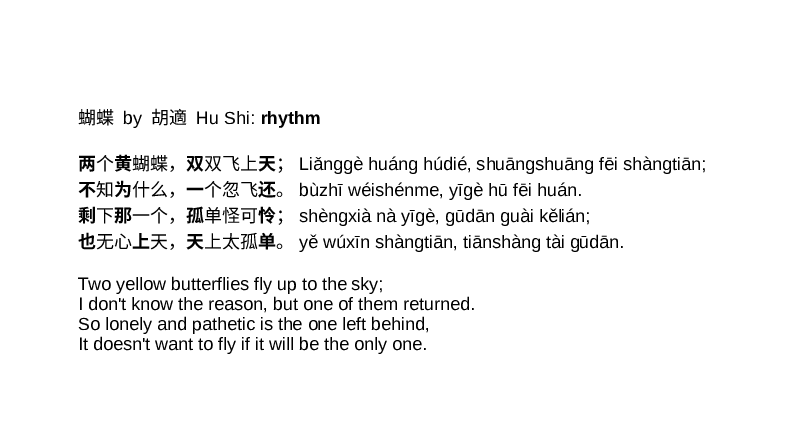

The first thing to notice is that it is twice as long as a tang poem or, if the tang poem is formed of two stanzas, is the same length, but the lines are stretched longer. That is, each individual image is described in ten characters rather than five. This is a necessary feature of vernacular chinese poetry, because in modern chinese, words can be more than one syllable long, so some terseness must be lost.

We’ve already touched on the use of punctuation. Here it is necessary to break up the longer lines into smaller chunks so that we can more easily maintain a rhythm as we read the poem aloud.

One of the most important aspects of Hu Shi’s work is the move towards iambic prosody. As mentioned, every syllable is stressed in classical chinese, but the variable length words in modern chinese encourage speakers to stress some syllables while omitting stress from others.

I think it is important to note here the limits of my chinese ability, but the way that i read it, Butterflies features a strong rhythm of four beats per line, two on either side of the comma. Before the comma, we split into sets of two or three syllables, two quavers or three triplet quavers, and after the comma, we read a set of four semiquavers and a minim. In other words, the pace of speech slowly picks up pace within each line before, in the final syllable, slowing right back down again. There are several ways we can interpret this as literary technique. One obvious suggestion would be that it represents the speed of a butterfly’s wings as it takes off from a leaf before, when finally airborne, it is able to soar on the air with no effort (although this is not an accurate depiction of how butterflies fly).

This pattern is consistent for the first three lines being two syllables followed by three syllables, but in the fourth line, we can see that we first get three syllables followed by two syllables. Breaking rhythm in the final line of a poem is a fairly common technique in western poetry and is often indicative of a lack of harmony in the image that the poem is describing.

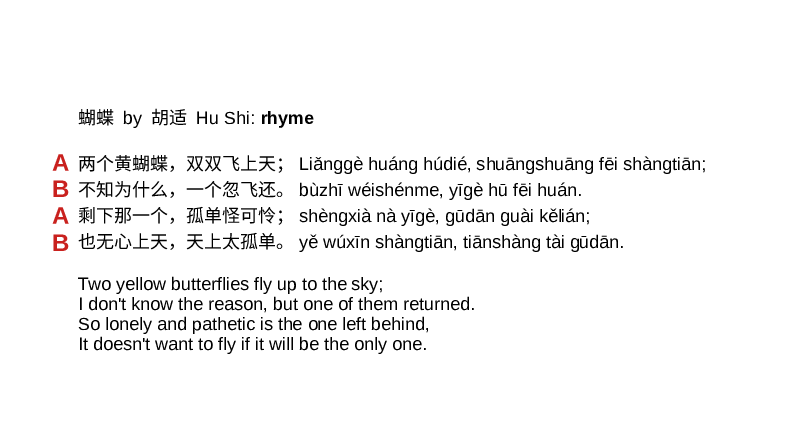

Another key characteristic of this poem is the rhyme scheme, a b a b. In tang dynasty poems, a single rhyme is emphasised throughout the poem (although this can sometimes be hard to see due to sound changes in the language). Adding to the complexity of tang poems, poems referencing or responding to other poems would need to keep the same rhyme scheme.

A b a b is a common western rhyme scheme. By not only opting out of the complex dynamics involved in rhyming tang poems, but replacing the whole kettle of fish with something distinctly western, Hu was taking a political stance on how he believed chinese poetry should be considered going forward. At this time, many young academics in china were looking for an explanation as to how the western countries had so rapidly managed to develop into world powers in a way that china hadn’t, despite being the centre of innovation for thousands of years, and the relationship between speaking, writing, and literature played a prominent part in the discourse. Unfortunately poetically, the playful rhymes in combination with the short length of the poem bring to mind a nursery rhyme rather than a serious poem.